Mindblown: a blog about philosophy.

China, State Capitalism, And The Rise Of State-aligned Corporate Power

Introduction In recent decades, the rapid rise of the People’s Republic of China has reshaped global economic, political, and technological landscapes. As China has grown into the world’s second-largest economy and a central node in global supply chains, questions have intensified about the long-term implications of its development model for the rest of the world.…

The Invisible Innovators: A History of Inventions Without Inventors — And What the Future Might Forget

Throughout human history, countless inventions have shaped the world so profoundly that they feel as if they have always existed. Yet many of these technologies have no known inventor. They emerged gradually, iteratively, anonymously — born not from the brilliance of one celebrated mind but from the accumulated effort of countless forgotten hands. From the…

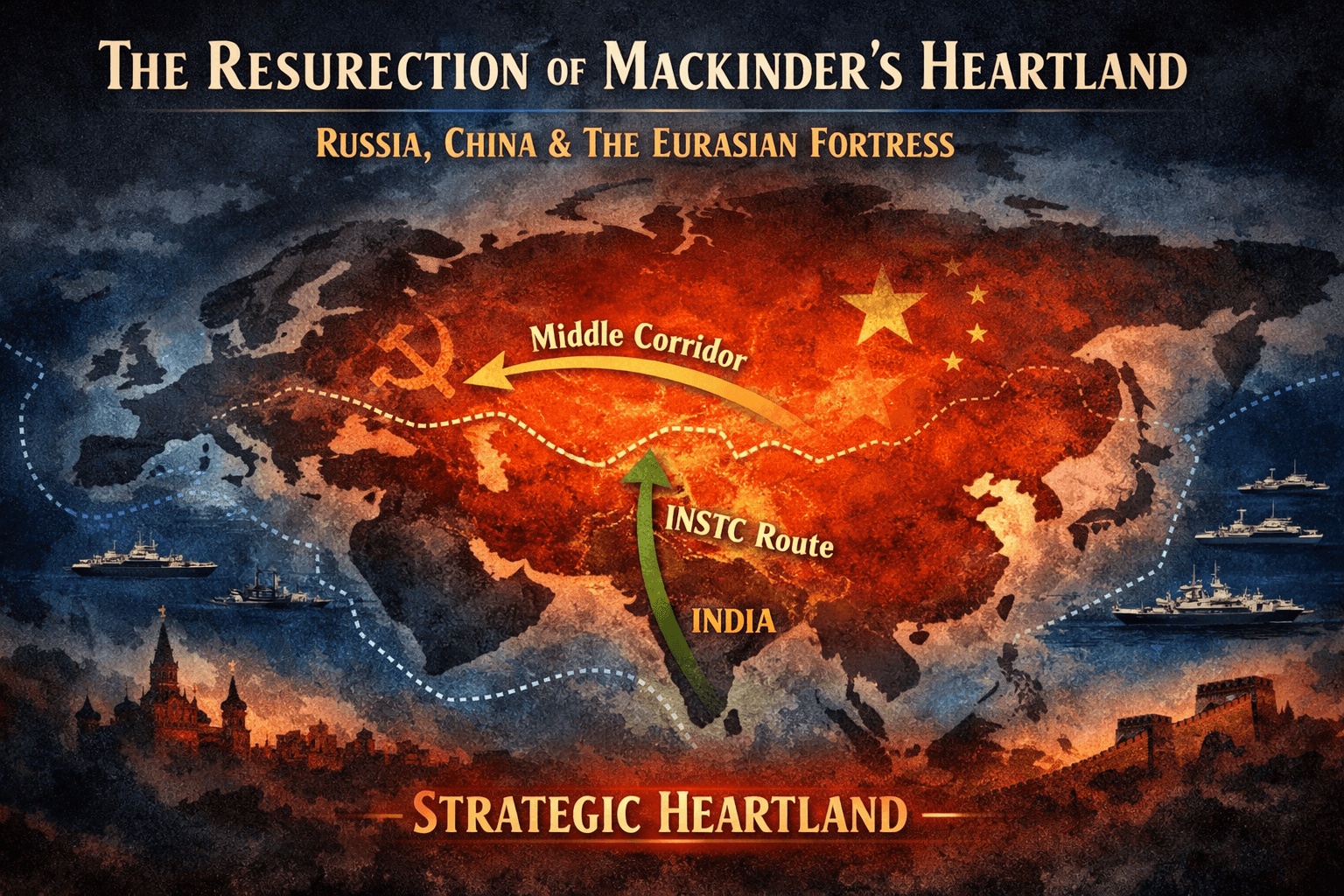

Chapter II: The Return of the Heartland Theory — The Eurasian Fortress

By the Geopolitical Desk The Resurrection of Mackinder’s Nightmare In 1904, the British geographer Sir Halford Mackinder presented a paper to the Royal Geographical Society titled The Geographical Pivot of History. His thesis was stark and terrifying to the maritime powers of the West: “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; Who rules the Heartland…

Chapter I: The Weaponization of Choke Points — From Strait to Silicon

By the Geopolitical Desk The Shift from Maritime to Molecular Geography For centuries, the concept of a “choke point” was exclusively maritime. It referred to the physical constriction of geography—the Strait of Malacca, the Suez Canal, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Bab el-Mandeb. These were the jugular veins of the global economy. Approximately 30%…

Changing Faces of Socialism

Socialism today is no less misunderstood than it was in the 1980s—often deliberately so. What its modern advocates describe as “socialism” is typically little more than cosmetic reform of capitalism, re-branded to appear humane while preserving centralised power. Yet history shows that whenever socialism moves beyond rhetoric into practice, it does not dismantle oppression—it merely…

Betancourt’s journey via theft

In a small, damp apartment in San Francisco de Yare, Venezuela, a 69-year-old woman named Selena Ramirez leaves her stove’s back burner running for hours while she performs household chores. This isn’t because she’s fond of keeping a flame alive, but because matches are too expensive, and in her situation, even the smallest daily conveniences…

The Perverted Ideal

The Perverted Ideal: How Good Intentions Become Weapons of Extraction (An examination of systemic hijacking across welfare states, healthcare, education, and beyond) (An examination of systemic hijacking across welfare states, healthcare, education, and beyond) I. The Universal Pattern of Institutional Capture Every great social idea begins with a moral impulse: no one should die for…

From Cheating to Essential: The Evolution of Calculators, Computers, and AI in the Classroom

For decades, teachers, parents, and education policymakers have wrestled with a recurring question: Where does learning end and cheating begin?Few tools demonstrate this debate more clearly than the calculator. Once banned from classrooms and considered academic sacrilege, calculators gradually became standard equipment—an expected item in every pencil case. The same story unfolded with computers, then…

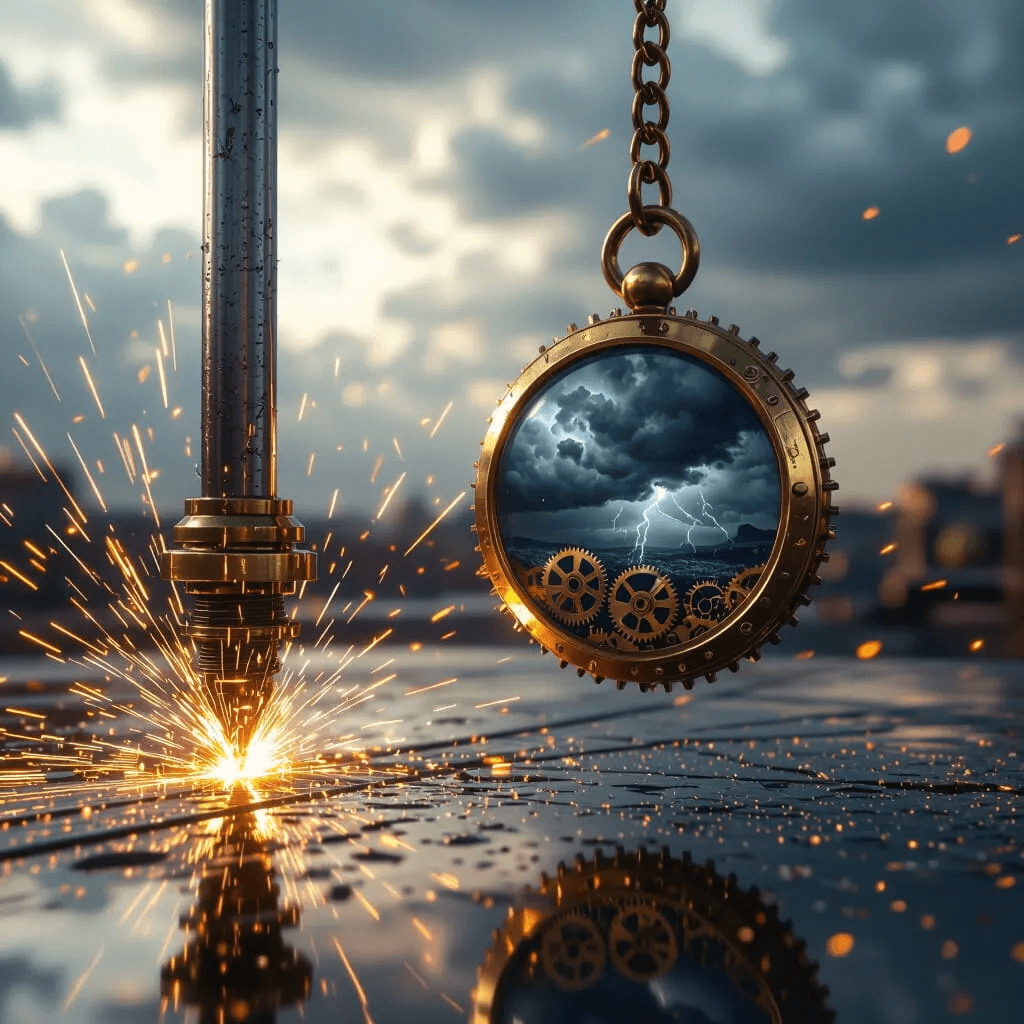

The Pendulum’s Arc: The Winder, The Swing, & the Distortion of History

Introduction: The Mechanics of Political Physics In podcast format History is rarely a straight line; it is a pendulum clock, rhythmic and relentless. We, the human race, are the winders. With every action, every war, and every ideological shift, we pull the weights, accumulating potential energy that inevitably demands a release. The laws of this…

Where Titans Flee to Escape the Taxman

How the world’s biggest companies are quietly relocating their global headquarters to pay almost nothing in corporate tax — and why it’s perfectly legal. Welcome, curious capitalist. While governments scramble to close loopholes and raise revenue, the smartest multinationals are doing something far simpler: they’re packing up their brass plaques and moving the entire headquarters…

Got any book recommendations?